When you step into the bigger and brighter Concourse B, set to open in summer 2021, the new artwork will probably catch a glimpse of you before you realize it’s gazing back. You’ll see it in the engraved steel portraits of some of Oregon’s most scenic places — a large graphic eye gradually appears in each landscape as you pass.

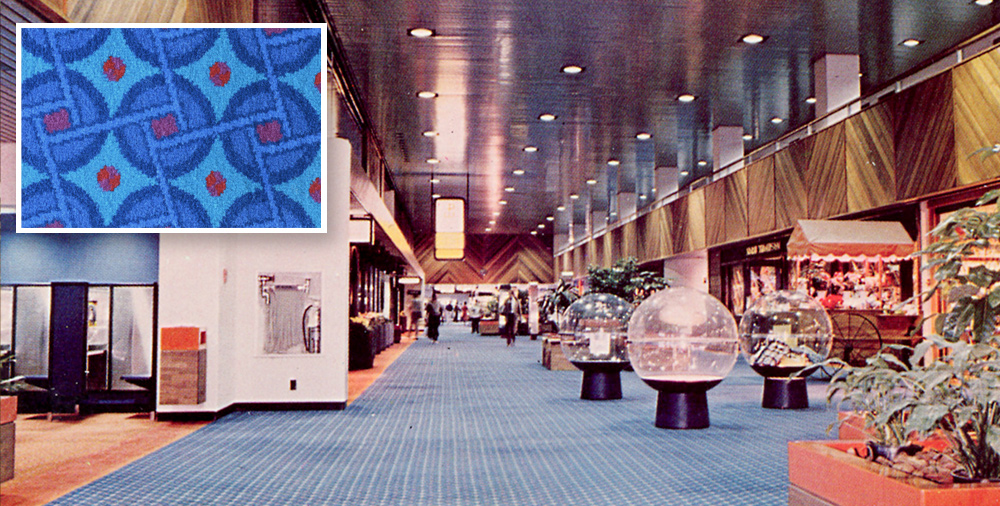

The optical illusion — technically known as a lenticular portrait — makes you not only pause to look at the art, but physically move around the space and change your vantage to see every dimension of it. That type of playful interaction is exactly what RYAN! Feddersen hopes you’ll experience when you see “Inhabitance,” an immersive installation coming soon to the Portland International Airport. The installation comprises three interconnected artworks: the “Sentinel” landscapes along with abstract “Habitat Tiles” and the gently rolling “Cloud Walk.” It’s the largest public art project to date from the Tacoma, Washington-based artist.

An enrolled member of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation and of mixed heritage, RYAN! draws inspiration from the region’s traditions and landscapes for these pieces, which highlight the biological diversity of the Pacific Northwest. She recently took a break from her studio to talk to us about her creative vision for Concourse B and the opportunities inherent in public art.

Let’s start with what’s next: You have a permanent installation coming in 2021 to Concourse B. What inspired the concept?

We live in a region that has some of the most diverse habitats in the world: beaches, grasslands, temperate rain forests, high desert, alpine mountains. So a lot of the inspiration for this new work comes from the Pacific Northwest’s biomes, which are astounding and vulnerable.

This piece is about imbuing these habitats with a very literal personhood, referencing eye mimicry and protective talismans to create this feeling of the land holding witness to us, that our gaze on the land is returned. It reflects Indigenous concepts of environmental personhood — and makes us think about how the land and the other life we share the planet with also have rights that we should not be violating.

How do you hope people will respond to the new PDX installation?

I hope it makes people feel differently about their relationship to the environment — that it emphasizes the scale and innate power and presence in the land. I also hope the piece makes people curious and that they find the shifting interaction with it exciting and surprising.

“Interactive” and “immersive” are two adjectives that often come up in relation to your work. In fact, you’ve said that your art “exists as people are interacting with it.” What makes accessibility and touchableness so integral to your artistic vision?

I know for me, as I’m making things, working with my hands allows me to understand my relationship with the subject matter on a deeper level. That’s one of the big motivations for why I emphasize interactive and often touchable work; I'm trying to provide an experience for people to get a deeper relationship with it.

I believe that art does not just live in an object — it's an experience we are sharing with other people through a variety of different methods. Now, that doesn't always have to be touchableness. In my early projects, that was the mode I often used because it’s very appropriate for temporary artwork. In this piece at Concourse B, interactivity is about your movement as a viewer, as what you see will be different depending on the perspective you view it from. It requires your action in order to activate the content of the artwork.

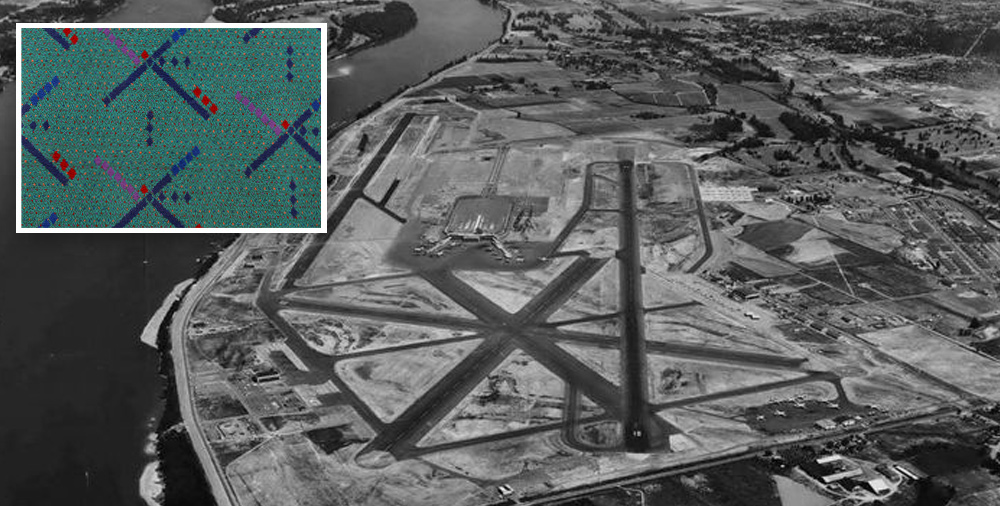

(Credit: RYAN! Feddersen)

(Credit: RYAN! Feddersen)

You’ve described some of your work as “traditional Plateau storytelling applied to contemporary issues.” What are some of the ways this plays out in your art?

The best example of this would be through a project called “Coyote Now.” This project looks at the trickster Coyote in Plateau lore as a continuous, contemporary figure. In these traditional stories, Coyote’s antics are a way for people to understand their actions and the consequences of those actions for other living things. He's kind of an antihero in that way, but he shows us how to be better. With “Coyote Now,” I’m thinking about the ways that we can use metaphor and imaginative storytelling to understand our life experience and how to best move forward.

(Credit: RYAN! Feddersen)

(Credit: RYAN! Feddersen)

As a kid, you wanted to be a Supreme Court justice when you grew up.

I don't know why I tell people that. [laughter] Back then, I thought it was the best way to enact change and participate in shaping our world, but there are many paths. I realized early on that it wasn’t a realistic path for me.

So what ultimately led you down the path of becoming a professional artist rather than a lawyer?

I don't have the story of being born with a pencil, as a lot of artists claim. I don't remember being that interested in art when I was very young — part of that may have been, to a certain degree, about access.

When I was a teenager I started getting interested in art and it was very, very healthy for me. It helped me process the world around me and how I saw myself within it. I started to realize art had power and that it was a way you could communicate with people about visions for the world and for change.

Creating public art presents a lot of challenges, especially in an environment like PDX where such a wide audience will experience your work. How does the venue — in this case, an airport — influence your creative process?

The interactions between the art and the audiences are a huge part of why I've pursued these types of projects. Museums and galleries are kind of self-selecting audiences and there’s limited accessibility into those spaces. I want to make work that’s for the community in a more direct way. People have a different feeling about their ownership of public spaces, which I find valuable.

And I do think about my public work differently. I know that people aren't necessarily choosing whether or not to see the art. I'm also thinking about how people are able to understand it. It’s important to me that the work is accessible to all audiences and not have barriers of needing an arts education or specific knowledge to be able to get something out of a piece.